Social Justice, Forgiveness and Dr. Seuss

By J.D. ECARMA

The biblical story of “Jonah and the whale” has become part of popular culture, ranking up there with Adam and Eve’s remarkable apple.

Jonah, a prophet ordered to bring a message of doom to a wicked city, tried to avoid God’s commands by hiding, a mistake that led to the whale* misadventure that has since been colorfully illustrated in so many children’s books. Man disobeys God, gets swallowed by whale and becomes a classic children’s craft for Sunday School.

If you haven’t read the Old Testament, here’s the end of the story: Jonah eventually made it to the city of Ninevah and warned of God’s impending judgment. “Ninevah will be overthrown before 40 days have passed,” he vowed.

In the passage, the very next sentence turns the story on its head. The people living in the wicked city God threatened to destroy “believed God, proclaimed a fast, and put on sackcloth, from the greatest to the least of them.” God relented, forgave them and did not bring disaster on Ninevah.

“Like a lot of us in 2017, he reacted to remorse, pleas for forgiveness and vows to change with … anger.”

How did Jonah react? Like a lot of us in 2017, he reacted to remorse, pleas for forgiveness and vows to change with … anger. Anger because the people of Ninevah deserved to be punished for what they did wrong. Anger because God had vowed to destroy them, not to embrace them and love them and forgive them.

Human nature finds it difficult to forgive. Too often, we would rather be able to stay angry and feel vindicated in our righteous indignation. We’ll freely tweet vitriol about someone and then ignore updates to the story when they apologize, change direction and put on (the 21st-century version of) sackcloth and ashes.

Over and over, meaningless stories emerge as cultural flashpoints that divide people into teams of right and left. Whether people are upset over Shakespeare or Kathy Griffin or inappropriate journalists or evangelical con men, they are extremely upset and fueled by righteous rage and they will be heard. Until the story blows over, and no one cares about Julius Caesar anymore except perhaps the actors who have been performing it using influences from their own time for centuries.

But each ephemeral story might as well be a shiv for the destruction it leaves behind before floating away. Who among us has not had relationships and friendships strained by politics? Who hasn’t felt that ideological divisions are too difficult and painful to overcome, especially when the differences sometimes come down to our very DNA, our humanity, our value as people?

We struggle to forgive and to ask for forgiveness because it can be almost as painful as the original hurt, and so we don’t, a wound bandaged instead of being cleaned and dressed properly.

A silly story about a school librarian’s rudeness to a First Lady recently left behind some cuts, neatly slicing people into right and left.

As part of National Read a Book Day, Melania Trump donated books to one school in each state, selecting 10 classic titles from Dr. Seuss, including childhood staples “The Cat in the Hat,” “Green Eggs and Ham” and “Oh, the Places You’ll Go.” One school librarian refused the gift, explaining that Dr. Seuss is “a bit of a cliché, a tired and worn ambassador for children’s literature” and that his books are steeped in “racist mockery.”

Accusing a beloved author of children’s books of being racist is the sort of issue that predictably divides America every day. Liberals can gather on one side to detail Theodor Seuss Geisel’s complicated and at times, undeniably problematic history, while conservatives can cluster on the other to be on the side of Dr. Seuss (which will always be the more winning side, at least for people with kids).

The truth is nearly always somewhere in the middle, too nuanced to be tweeted effectively and too inconveniently complex to make a good talking point.

Quartz recently detailed Geisel’s story while making the case for keeping Dr. Seuss at the ready, saying, “in pitting Seuss against social justice, Soeiro [the school librarian] misses one of the fundamental reasons his rhyme-saturated books have endured, and why we should keep reading them to kids.” The piece made a progressive case for Dr. Seuss and the “universality” that picture books offer when kids can escape into a world of pure imagination and green eggs and ham.

Before he wrote Hop on Pop, Geisel was a New York cartoonist who churned out hundreds of war propaganda cartoons that included patriotic and pro-civil rights messages. One of his anti-isolationist war cartoons even resurfaced in recent years as part of the fight for refugees right before Republicans brought back the “America First” movement.

But some of his cartoons were inarguably racist. Despite his inclusivity for black and Jewish people, Geisel didn’t seem to believe in the civil rights of Japanese-Americans and advocated for them to be put in internment camps during World War II. He left his fingerprints on a dark and shameful chapter of American history with cartoons depicting Japanese people as ugly, inhuman stereotypes that were intent on destroying America and were little better than vermin.

Geisel is believed to have had a change of heart after the war. He visited Japan in 1953, meeting schoolchildren around the country as part of his research for a Life magazine article.

“I conceived the idea for Horton Hears a Who from my experiences there,” he said in an interview. “Japan was just emerging, the people were voting for the first time, running their own lives—and the theme was obvious: ‘A person’s a person no matter how small.’”

Geisel dedicated the book to his friend Mitsugi Nakamura, dean of Doshisha University in Kyoto, who influenced both Geisel’s research in Japan and the story about Horton.

First Lady Michelle Obama reads “Cat in the Hat” at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., March 2, 2010. (Credit: White House)

First Lady Michelle Obama reads “Cat in the Hat” at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., March 2, 2010. (Credit: White House)

Today, most people remember Geisel’s message about inclusivity, the one they learned as kids reading Horton Hears a Who over and over. The book has long been interpreted as a call for equality and a reminder of human value, and its message of “a person’s a person” has even been adopted by the pro-life movement in the past few decades.

If Geisel had endured a 2017-level reaction to his racist cartoons at the time, he might not have been able to visit Japan. His career would have taken a devastating hit in America, and countless children likely would have missed out on his books. Fortunately, he lived before social media mobs existed to drag someone’s name through the mud and make it nearly impossible for anyone to experience growth and grace. He had space to think; to grow as a person and visit another country; and to work out his own salvation by writing an enduring children’s classic.

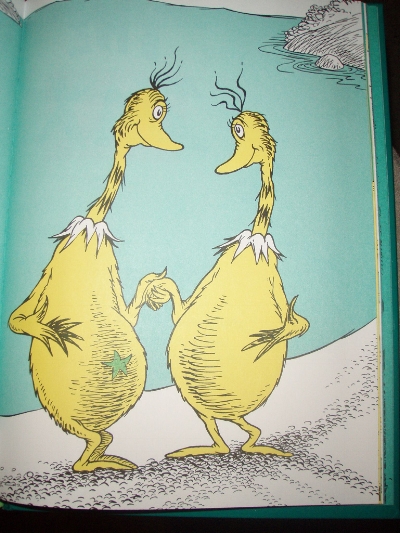

Credit: Flickr Creative Commons

Credit: Flickr Creative Commons

The Sneetches is another Dr. Seuss book that teaches a message of equality and acceptance. In the story, star-bellied and plain-belled “sneetches” live on the beaches, and those with stars think they’re better than those without. They finally realize that they’re all the same – and they’re much happier being equal.

“The day they decided that Sneetches are Sneetches

And no kind of Sneetch is the best on the beaches

That day, all the Sneetches forgot about stars

And whether they had one, or not, upon thars.”

Did Geisel sneak messages into his children’s books the way he had earlier used propaganda to promote American patriotism and liberal ideals in cartoons? He admitted in later years that yes, his books were quietly propagandistic.

“The morals sneak in, as they do in all drama,” he said. “Every story’s got to have a winner, so I happen to make the good guys win.”

*Yes, the Bible describes the creature that swallowed Jonah as a “great fish,” but “whale” is usually what people reference.